[box type=”bio”] Learning Point of the Article: [/box]

In-continuity high-grade cubital syndrome can be treated with SETS AIN to ulnar motor nerve outcome with good success.

Case Report | Volume 8 | Issue 5 | JOCR September – October 2018 | Page 25-28| Geoff Jarvie, Mathilde Hupin-Debeurme, Zafeiria Glaris, Parham Daneshvar. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1194

Authors: Geoff Jarvie[1], Mathilde Hupin-Debeurme[1], Zafeiria Glaris[1], Parham Daneshvar[1]

[1]Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of British Columbia St. Paul’s Hospital – 3rd Floor, Room 339A 1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC V6Z 1Y6, Canada.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Geoff Jarvie,

MD, MSc212 – 2050 Scotia Street, Vancouver, BC, V5T4T1, Canada.

E-mail: geoffjarvie@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: The supercharged end-to-side (SETS) anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) to ulnar nerve transfer has been recently described for severe cubital tunnel syndrome. Previous studies have suggested that this technique augments or “babysits” the motor end plates until reinnervation occurs; however, it has more recently been suggested that reinnervation occurs by the donor nerve as evidenced in animal research.

Case Report: We present two cases of rapidly progressive ulnar neuropathy who underwent a SETS AIN to ulnar nerve transfer who demonstrated improvement in their electrodiagnostic studies in addition to improvement in their clinical and patient-reported outcome’s scores postoperatively.

Conclusion: Our findings provide further evidence that previously demonstrated in the literature that the SETS does more than “babysit” the motor end plates, but that there is axonal growth along the new pathway.

Keywords: Ulnar nerve, cubital tunnel syndrome, nerve transfer.

Introduction

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the most common compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve and if left untreated, it can result in significant clinical deficits [1]. Time for motor end plate reinnervation and absolute number of regenerated axons are determinants of the functional recovery in peripheral nerve injury. Like any other high ulnar nerve injury, incomplete recovery is anticipated with severe cubital tunnel syndrome if the time elapsed to regenerate the nerve is longer than the intrinsic muscles motor end plates life span [2]. Supercharged end-to-side (SETS) nerve transfer for severe cubital tunnel syndrome is a recently described technique, which involves augmenting the ulnar motor branch with the terminal branch of the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) [3, 4].The AIN is the donor nerve of choice for recovering of some ulnar nerve intrinsic function in complete proximal ulnar nerve injuries and is most commonly used in an end-to-end coaptation [5].In moderate or proximal injuries, Barbour et al. [6] employed a SETS nerve transfer technique to enhance, or “supercharge,” the motor fascicles of the ulnar nerve. Previous studies have suggested that this technique augments or “babysits” the motor end plates until reinnervation occurs; however, it has more recently been suggested that reinnervation occurs by the donor nerve as evidenced in animal research[7, 8, 9].Davidge et al. [10]are the largest clinical study which provides further support to this hypothesis and demonstrated reversal of intrinsic muscle atrophy. In the present report, we describe two cases with electromyographic findings where this transfer was performed to successfully treat rapidly progressive ulnar neuropathy, suggesting the hypothesis of reinnervation by the donor nerve.

Case Report

Case 1

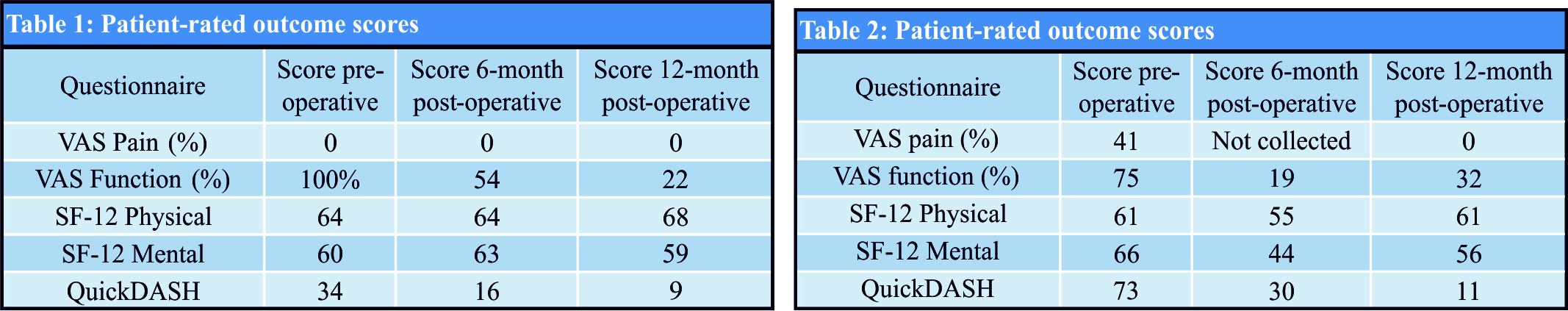

A 57-year-old right-hand dominant female with a history of early Parkinson’s disease presented with a 4-month history of progressive and persistent paresthesia along the ulnar nerve distribution, associated with difficulty in grasping and pinching activities. She had no history of trauma, illness, or pain anywhere in her hand, wrist, elbow, or shoulder. On physical examination, she had dense paresthesia with no two-point discrimination involving the ulnar two digits and the dorsal ulnar aspect of the hand. Significant hypothenar and first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle wasting associated with loss of one grade of strength (4/5) compared to the contralateral side were present. There was noulnar nerve instability over the medial epicondyle. Provocative maneuvers including Tinel’s testing over the cubital tunnel and Guyon’s canal, as well as elbow flexion test were interestingly found to be negative. Nerve conduction studies showed evidence of severe ulnar neuropathy at the level of the elbow, with evidence of significant axonal loss. Specifically, it was found that there were a diminished amplitude and conduction velocity at the elbow level for both sensory and motor responses, prolonged F-wave latencies, and active denervation of the FDImuscle with positive sharp waves and fibrillations. The patient underwent cubital tunnel ulnar nerve release, ulnar nerve anterior transposition, and Guyon’s canal release along with an SETS AIN to ulnar motor nerve transfer as described by Barbour et al. Postoperatively, the patient was instructed to follow a specific motor nerve reeducation rehabilitation program and was fitted with serial casting in her affected fingers to improve the contractures. Nerve recovery was monitored clinically and with repeated electrodiagnostic studies at 6 months and at1year postoperatively. The patient-rated functional outcome instruments were administered preoperatively and at 1year postoperatively.  At 6 months postoperatively, the patient had a modest improvement in the strength of her first dorsal interosseous 4+/5 strength. Nerve studies at that time showed the absence of the right ulnar digit 5 sensory response, and no electrodiagnostic improvements in the amplitude of hypothenar motor response compared to preoperatively. At the 1-year mark, there was a significant improvement in her right ulnar neuropathy with the EMG showing good innervation with large amplitude motor unit potentials in the FDI and abductor digitminimi. The nerve conduction studies demonstrated an improved ulnar motor conduction velocity across the elbow and a normal median motor nerve velocity. The ulnar F-wave latency was found to be normal. Hypothenar motor amplitude was still found to be reduced and the ulnar digit 5 sensory response was found absent. The strength in her hand was found to have increased along with an improved bulk in the intrinsic musculature. There was still significant decreased sensation in her ulnar nerve distribution. At 2years postoperatively, the patient had recovered full intrinsic muscle strength 5/5 and muscle bulk was equal to the contralateral side. She had persistent PIP contractures that failed to improve with serial casting and hand therapy, with a flexion contracture of 60 degrees of the 5th digit and 30 degrees of the 4th digit.She underwent an open contracture release and tenolysis of the 5th PIP joint and a closed manipulation of the 4th PIP joint. Both digits recovered motion and at 3 months postoperatively had a 15-degree flexion contracture. The patient-rated outcomes obtained at 1 year postoperatively showed a markedly improved overall pain and function compared to pre-operative levels (Table 1).

At 6 months postoperatively, the patient had a modest improvement in the strength of her first dorsal interosseous 4+/5 strength. Nerve studies at that time showed the absence of the right ulnar digit 5 sensory response, and no electrodiagnostic improvements in the amplitude of hypothenar motor response compared to preoperatively. At the 1-year mark, there was a significant improvement in her right ulnar neuropathy with the EMG showing good innervation with large amplitude motor unit potentials in the FDI and abductor digitminimi. The nerve conduction studies demonstrated an improved ulnar motor conduction velocity across the elbow and a normal median motor nerve velocity. The ulnar F-wave latency was found to be normal. Hypothenar motor amplitude was still found to be reduced and the ulnar digit 5 sensory response was found absent. The strength in her hand was found to have increased along with an improved bulk in the intrinsic musculature. There was still significant decreased sensation in her ulnar nerve distribution. At 2years postoperatively, the patient had recovered full intrinsic muscle strength 5/5 and muscle bulk was equal to the contralateral side. She had persistent PIP contractures that failed to improve with serial casting and hand therapy, with a flexion contracture of 60 degrees of the 5th digit and 30 degrees of the 4th digit.She underwent an open contracture release and tenolysis of the 5th PIP joint and a closed manipulation of the 4th PIP joint. Both digits recovered motion and at 3 months postoperatively had a 15-degree flexion contracture. The patient-rated outcomes obtained at 1 year postoperatively showed a markedly improved overall pain and function compared to pre-operative levels (Table 1).

Case 2

A 58-year-old right-hand dominant male presented with a severe and progressive right ulnar neuropathy. He had no history of trauma, illness, or pain anywhere in his hand, wrist, elbow, or shoulder. He experienced progressive numbness and paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution and developed significant weakness with grip associated with rapid wasting of his intrinsic muscles. Clinically, wasting of his intrinsic muscles was prominent (Fig. 1) and associated with a loss of two grades of strength (3/5) in his FDI and hypothenars. Sensation was decreased along with abnormal two-point discrimination on the ulnar two digits and on the ulnar dorsum of the hand. He had a mildly positive Tinel’s at the elbow and the ulnar nerve was found to be subluxating. Nerve conduction studies demonstrated prolonged distal latency and F-wave latencies, and the hypothenars demonstrated significant denervation with a motor amplitude of 1mV. The patient underwent the same surgical procedure, post-operative reeducation, and follow-up regimen as described for the first case. At 7months postoperatively, the patient still had 4/5 strength in his FDI and hypothenar muscle testing. He had mildly improved sensation and pinprick testing in the ulnar nerve distribution. The post-operative nerve studies performed at 7 months showed significant improvement in motor amplitude for FDI and hypothenar testing to 2.4mV. Conduction velocity across the elbow remained slow. He still had an absence of the right ulnar finger 5 sensory response. Clinically, at the 1-year mark, the patient presented significant recovery of his intrinsic muscle bulk, increased finger abduction, and improved strength to 4+/5 (Fig. 2). His sensation testing remained altered but improved. Nerve conduction studies at 1 year confirmed our clinical impression, showing ulnar nerve reinnervation with large amplitude motor unit potentials in the FDI, increased motor amplitudes in hypothenars to 4.1mV, and improved conduction velocity across the elbow while sensory response remained absent. The patient-rated outcomes obtained at 10 years postoperatively showed a markedly improved overall pain and function compared to pre-operative levels (Table 2).

Discussion

Our findings provide further evidence that previously demonstrated in the literature by Davidge et al.[10]that the SETS does more than “babysit” the motor end plates, but that there is axonal growth along the new pathway. Their study reviewed 55 patients with in-continuity lesions that showed axonal loss who underwent a SETS AIN to ulnar motor nerve transfer. The results were promising in that they showed significant improvement in terms of motor strength recovery and patient-rated functional outcome scores. They suggested that the ulnar nerve recovery was in part a result of the transfer based primarily on the time frame of recovery that being rapid recovery if the dysfunction was a result of ischemic injury, recovery in approximately 3 months if there was demyelination, 4–7 months for the nerve transfer and approximately 18 months if there was axonal regrowth from elbow level. They found the majority of improvement in their patients was between their 1–3 and 3–6 months follow-up, suggesting the nerve transfer was in part responsible for the improvement. They additionally presented the findings in one patient of a nerve conduction study postoperatively that demonstrated stimulation of the median nerve resulted in the first dorsal interosseous firing, thus providing further support that the nerve transfer was in part responsible for the motor recovery. Both our study patients demonstrated improvement within the time frame that would be expected for the nerve transfer similar to that showed by Davidge et al. [10]. In addition, we suggest that the lack of sensory recovery, based on electrodiagnostic studies, while there was significant motor recovery provides further evidence that the transfer is responsible for the recovery noted. If the decompression at the elbow was the major source of their improvement, there should have been a proportional improvement in their sensation, whereas if the nerve transfer to the motor branch of the ulnar nerve alone there would be a disproportionate recovery of motor function compared to sensation. Previously in the literature, patients have been followed clinically alone, whereas our findings also show EMG and nerve conduction improvement. Ideally, the electrodiagnostic study’s findings would have been done similarly to the one patient in the Davidge et al. [10].Study with stimulation of the median and ulnar nerve to demonstrate that in part FDI recovery is a result of the transfer.

Conclusion

Our results provide further support and agree with the current literature that SETS AIN to motor ulnar nerve is an option for an in-continuity ulnar nerve injury with axonal loss. This procedure may not only “babysit” the end plates, but rather potentially provides reinnervation. Further studies need to be performed to demonstrate the latter.

Clinical Message

In-continuity high-grade cubital syndrome can be treated with SETS AIN to ulnar motor nerve outcome with good success.

References

1. Dy C, Mackinnon S. Ulnar neuropathy: Diagnosis and management. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2016;9:178-84.

2. Patterson J. High ulnar nerve injuries: Nerve transfers to restore function. Hand Clin 2016;32:219-26.

3. Brown JM, Mackinnon SE. Nerve transfers in the forearm and hand. Hand Clin2008;24:319-40.

4. Brown JM, Yee A, Mackinnon SE. Distal median to ulnar nerve transfers to restore ulnar motor and sensory function within the hand: Technical nuances. Neurosurgery 2009;65:966-77.

5. Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Distal anterior interosseous nerve transfer to the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve for reconstruction of high ulnar nerve injuries. J ReconstrMicrosurg2002;18:459-64.

6. Barbour J, Yee A, Kahn L, Mackinnon S. Supercharged end-to-side anterior interosseous to ulnar motor nerve transfer for intrinsic musculature. J Hand Surg Am2012;37A:2150-9.

7. Kale S, Glaus S, Yee A, Nicoson MC, Hunter DA, Mackinnon SE, et al. Reverse end-to-side nerve transfer: From animal model to clinical use. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36A:1631-9.

8. Farber S, Glaus S, Moore A, Hunter D, Mackinnon S, Johnson P. Supercharge nerve transfers to enhance motor recovery: A laboratory study. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38:466-77.

9. Fujiwara T, Matsuda K, Kubo T, Tomita K, Hattori R, Masuoka T, et al. Axonal supercharging technique using reverse end-to-side neurorrhaphy in peripheral nerve repair: An experimental study in the rat model. J Neurosurg2007;107:821-9.

10. Davidge K, Yee A, Moore A, Mackinnon S. The supercharge end-to-side anterior interosseous-to-ulnar motor nerve transfer for restoring intrinsic function: Clinical experience. PlastReconstr Surg 2015;136:344-52.

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Geoff Jarvie | Dr. Mathilde Hupin-Debeurme | Dr. Zafeiria Glaris | Dr. Zafeiria Glaris |

| How to Cite This Article: Jarvie G, Hupin-Debeurme M, Glaris Z, Daneshvar P. Supercharge End-to-Side Anterior Interosseous Nerve to Ulnar Motor Nerve Transfer for Severe Ulnar Neuropathy: Two Cases Suggesting Recovery Secondary to Nerve Transfer. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2018. Sep-Oct ; 8(5): 25-28. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com